Designing something ‘almost useful’

How designing for the purpose of "interest" rather than "usefulness" expands our student's skill sets and potential for future impact.

Our lives are dictated by the many machines that surround us. From a clock to a computer, machines are an integral part of our lives, and even more so when you work in a Fab Lab! As part of the Master in Design for Emergent Futures (MDEF) programme, our students explore the complexity and curiosity of machines from the perspective of Chindōgu (珍道具), a Japanese approach to designing and making ingenious everyday gadgets which address problems which do not exist, resulting in an almost useful machine.

This article, a collaboration between Daphne Gerodimou, Designer & Future Learning Researcher and Cesar Rodriguez, Communications & Researcher at Fab Lab Barcelona, explains the process of designing and building Chindōgu machines in the Fab Lab by students MDEF students in the classes ‘Almost Useful Machines’ and ‘Unpacking intelligent Machines’.

A crash-course in everything ‘almost useful’

Tasking our Master in Design for Emergent Futures (MDEF) students to create something ‘almost useful’ is paradoxical. In the course, we challenge our students to design actionable change which will have a tangible and positive impact on the future and present- so why would we want them to design and create something that is only ‘almost useful’?

“The Almost Useful Machines” is a practical and intensive two-weeks experimental digital fabrication course designed for the MDEF 1st term. It stands as an introduction to basic fabrication concepts and therefore to the Fab Lab environment. It has been designed to fill knowledge gaps and prepare students for their Fab Academy experience in the next term.

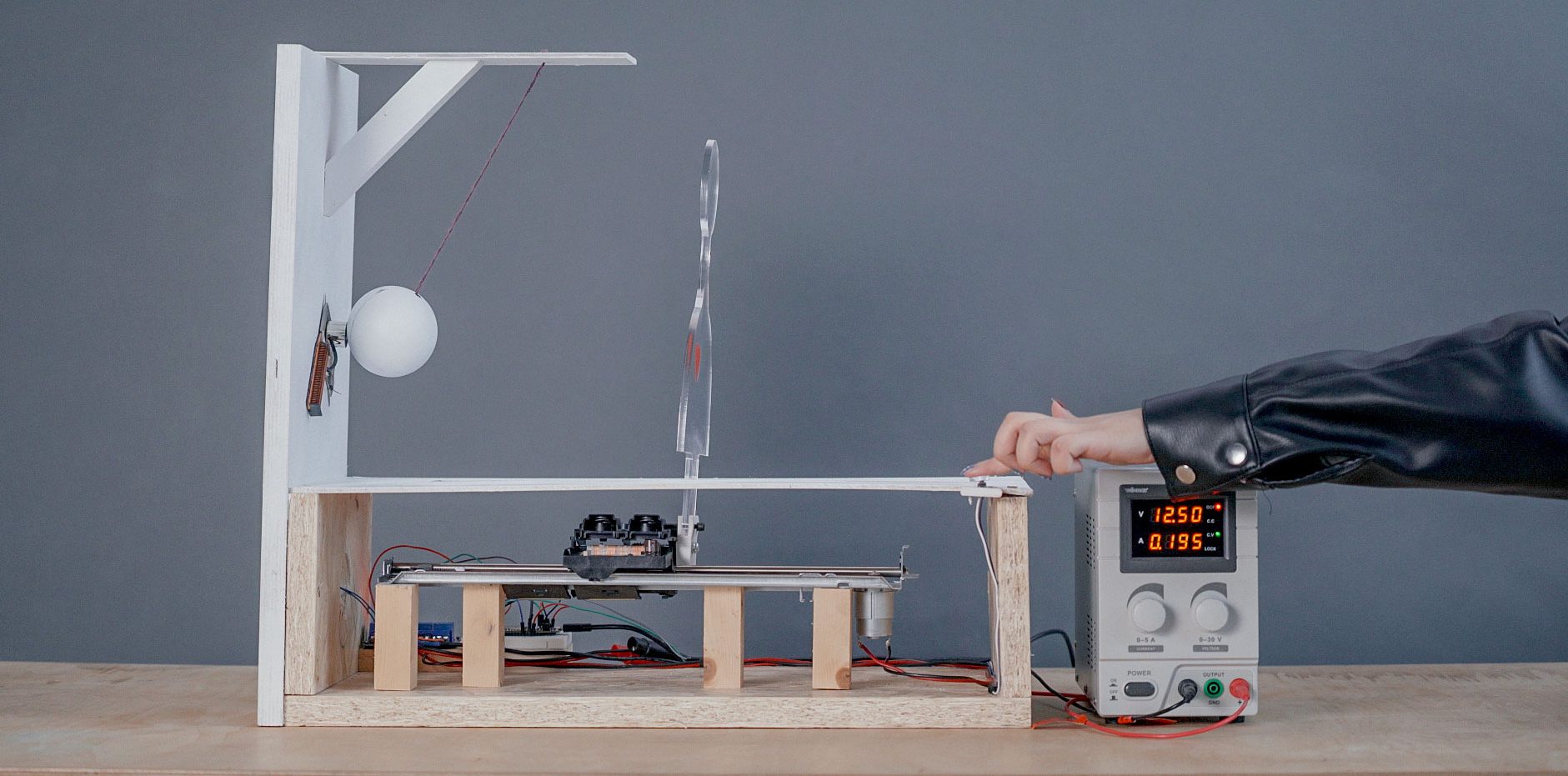

Following Fab Academy’s learn by doing mentality, the MDEF students are challenged with the task of conceptualising, designing and ultimately fabricating a prototype of ‘an almost useful machine’ using digital fabrication practices and electronics. The active learning methodology of the course is based on the practice and spiral development, designed to encourage the creativity and imagination of the participants, as well as stimulate the search for tools and solutions.

Integrating a hybrid education model

Following COVID-19 restrictions, this year’s course had to be adapted in order to fit the needs of the hybrid-model (digital & physical learning) that both IAAC and Fab Lab Barcelona have implemented into their learning courses. Specifically for the MDEF course, four students were following the classes online and therefore an extra level of complexity was added to the design and planning of an intense hands-on digital fabrication workshop.

A special research team within Fab Lab Barcelona was created and dedicated to adequately respond to the challenges imposed by executing the hybrid-model of learning. Whilst it adds complexity to an already complex and versatile design course, it also stands as a great opportunity for experimentation and therefore allows for the emergence of novel learning landscapes integrating both physical and digital tools. As a case study “The Almost Useful Machines” has been one of the most interesting and has provided the research team with valuable insights concerning practical hybrid courses.

Our initial assumption regarding the needs of the hybrid-model course was to use as much of the hybrid class infrastructure as possible. We focused primarily on preparing the equipment for the classroom, setting the standard screen, camera and speakerphone but also using as much of the additional equipment we had in our disposal, such as smaller portable cameras for the student’s personal computers and a moving camera holder hanging from the ceiling of the classroom that instructors would navigate according to the happenings of the class. The intention was to create for the remote students as many visual perspectives of the classroom as possible in order for them to actively follow and participate in the physical activities.

Creating a ‘classroom feel’ for remote learners

In terms of designing the course, a crucial parameter was the formation of working groups, not only in order to best integrate the remote students but also to facilitate the overall learning experience for the entire of the class. Taking into consideration that this was the first practical course including technical knowledge and fabrication and that students come from various disciplines and backgrounds, we had to assume that their knowledge and skills will vary accordingly.

We assumed that it would be beneficial to create working groups with the notion of equally distributing student’s skills in order to ensure that every group, collaboratively, has the skill-set required to complete the challenge. In this way, remote students would have a more concrete role and be able to equally contribute to the process. We were somewhat fortunate in the sense that the four remote students were more comfortable with coding and electronics, the two skills mostly lacking in the class. This proved to be a crucial factor in terms of facilitating their integration as the course progressed.

For the creation of the groups, the collaborative platform Miro was used in an effort to include the remote students in a synchronous manner. Each student had a dedicated skill-set template, designed to facilitate individuals to reflect on their strongest and weakest skills, which they would later use to form groups. The Miro board included various templates dedicated to different collaborative tasks and exercises that took place during the course.

Rebuilding from ‘intelligent machines’

During the first week, the students were introduced to basic concepts about technology and electronics through the exercise of dismantling “intelligent” machines, from printers to digital projectors and mobile phones, in the intention of unlocking some technological black boxes. The objective was, firstly, to understand the logic behind everyday machines and get familiar with various mechanical and electrical components and their function. The second step was to create an inventory of these components in view of repurposing them later on for their own machines.

The second week, students had to focus on the ideation of the machine’s concept in an effort to make something possibly meaningful but not purpose oriented. Adding the parameter of uselessness was important as the team wanted to liberate students from the “solutionism” mentality and encourage creativity and playfulness. Since it was the first time students were faced with complex technological concepts and fabrication processes it would be rather overwhelming to demand full functioning purposeful prototypes. Instead, the focus should be concentrated on the fabrication process itself and the skills and knowledge acquired through designing and iterating.

Adapting to make for a better learning experience

As the course progressed we inevitably encountered several challenges concerning the hands-on hybrid class. One of the first problems to emerge was the difficulty for the hybrid groups to communicate during class due to the noise from the surrounding environment. Since four out of five groups contained remote students and they all needed to discuss their ideas simultaneously via zoom, it inevitably resulted in confusion and annoyance generated by the chaotic and noisy classroom. Due to this, some students requested another classroom where they could isolate for a period of time to discuss. The team had to coordinate and come up with a quick solution, asking for availability of another space in IAAC facilities. The noise factor, even though in retrospect seems rather obvious, was not a parameter we took into consideration when planning the class and is one of our most valuable insights for planning hybrid practical workshops.

At this point we realised that because of in-situ technical difficulties presented by the hybrid model, the schedule and objectives of the course would have to be constantly adjusted in order to adapt to the actual flow of the class. The layer of complexity added by the hybrid format subsequently resulted in removing some of the complexities of the learning challenge. The instructor’s team had to, in a sense, compromise the premises of the final outcome to ensure that the essence of the learning objectives remained intact without over-stressing and exhausting the students.

This course emphasised the importance of establishing strong communication networks between faculty and students in view of forging a reciprocal relationship that serves both the objectives of the course, but also the needs and emotional stability of the learners. It also emphasised the significance of a flexible and adaptive learning strategy especially when dealing with complex courses such as “The Almost Useful Machines”.

Applying a new skillset

In the paradox of designing something ‘almost useful’ lies the beauty of the experiment. By unshackling our students from the constraints established in typical design education, a project brief for which the students respond to directly in a manner which addresses the problem at hand, they are able to explore both their imaginative prowess, as well as a new skill set- the ability to draw attention.

When crafting an ‘almost useful machine’ the objective is never to make something useful; it’s to make something interesting, something which will give people pause and make them think about what you have designed and maybe even ask why. With this skill set, the students will apply new techniques to their own thesis projects allowing them to gain public interest and have a greater impact on the future.

Authors

Daphne Gerodimou

MDEF Assistant